The songs of the Griffun

Francis Greene

I have been asked to write a few serious words for a

serious publication about my visit to the Griffin in 1992, but I find the

task difficult. How can one write dispassionately of an event which evoked

strong and various passions, and of which the memory has so little

relation to everyday reality, is so improbable and dreamlike?

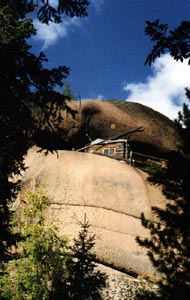

The

Griffin is a natural rock fissure which has been transformed into

something between a cave and an izba. It is at the summit of one of the

curious rock pinnacles, the "Stolby", which can be ascended only

by skilled specialist climbers. I am not such a one and I was taken up

there as a piece of luggage. I was in good hands, but for me, with no

sense of balance and no head for heights, the prospect of such a journey (for

snow still clung to the glassy rock) was indeed alarming. Perhaps the last

few feet of the ascent were the worst. The drawbridge or "doorlock"

to this eyrie is a thin wooden spar spanning an abyss: when removed the

route is barred to any but a very exceptional "stolbist". I

remember well the elation I experienced on arriving at my destination

after successfully crossing its drawbridge, damped only by the realisation

that to fulfill any call of nature I would have to find my way all the way

back down to the bottom! The

Griffin is a natural rock fissure which has been transformed into

something between a cave and an izba. It is at the summit of one of the

curious rock pinnacles, the "Stolby", which can be ascended only

by skilled specialist climbers. I am not such a one and I was taken up

there as a piece of luggage. I was in good hands, but for me, with no

sense of balance and no head for heights, the prospect of such a journey (for

snow still clung to the glassy rock) was indeed alarming. Perhaps the last

few feet of the ascent were the worst. The drawbridge or "doorlock"

to this eyrie is a thin wooden spar spanning an abyss: when removed the

route is barred to any but a very exceptional "stolbist". I

remember well the elation I experienced on arriving at my destination

after successfully crossing its drawbridge, damped only by the realisation

that to fulfill any call of nature I would have to find my way all the way

back down to the bottom!

But, as I was soon to learn, the Griffin stands for

much more than a physical challenge - a physical challenge which is,

almost like ballet, also a form of art. I am one of the least

distinguished (as well as one of the most timorous) of the guests to have

been taken there. The Griffin, it transpires, is an international cultural

meeting centre (and I hope the small Union Jack which I had brought with

me is still hanging among many other flags on its wall). Most eminent of

its guests have been the "bards" - those poet composers who kept

the soul of Russia alive through dismal repressive times of forced

conformity. The great Yuli Kim has been here and has sung here, so has the

fine (albeit lesser) poet-singer Shcherbakov and another singer of world

renown, Elena Kambourova.

I

was soon to discover that this lofty (in all senses) tradition is

maintained. I was treated to what can truly be described as the most

exclusive concert performance in the most inaccessible concert hall in all

the world. Here I heard not only the classic 20th century guitar

masterpieces - of Okudzhava, Kim and others - but many `author's songs',

fine in themselves and performed by their composers with exceptional

virtuosity. One male voice had a purity and power which forced the very

rock to resonate in sympathy. I

was soon to discover that this lofty (in all senses) tradition is

maintained. I was treated to what can truly be described as the most

exclusive concert performance in the most inaccessible concert hall in all

the world. Here I heard not only the classic 20th century guitar

masterpieces - of Okudzhava, Kim and others - but many `author's songs',

fine in themselves and performed by their composers with exceptional

virtuosity. One male voice had a purity and power which forced the very

rock to resonate in sympathy.

To return to earth - how can the Griffin be designated? As a

rockclimber's idyll? No doubt it is so, but for me that is far from the

greatest of its charms. As a historic monument to the resistance of

individualism to state power? There are remarkable accounts, yet to be

fully chronicled, of Soviet military helicopter attacks on the high nests

of the Stolbisty. No. The Griffin symbolises another sort of originality,

the one that is exemplified by any and every tight-knit group of

exceptionally talented people - a distinctiveness of the sort that has

given rise to scores of descriptive terms ending in "-ism", each

referring to the blazing of a trail in some new and spontaneous direction

for literature, poetry, art or music. Here on a snowy spire of rock above

the Krasnoyarsk taiga I was moved almost to tears by a blend of poetry and

music brilliantly performed by its poet-musicians - all of whom were also

skilled rock-climbers. I have met experiences of this sort elsewhere in

Russia but never with greater intensity. This then is what the Griffin has

come to mean for me, and it has been well named: the griffin of mythology,

offspring of a lion and an eagle and dedicated to the sun, was made the

guardian of hidden and sacred treasures.

|

|